Definition

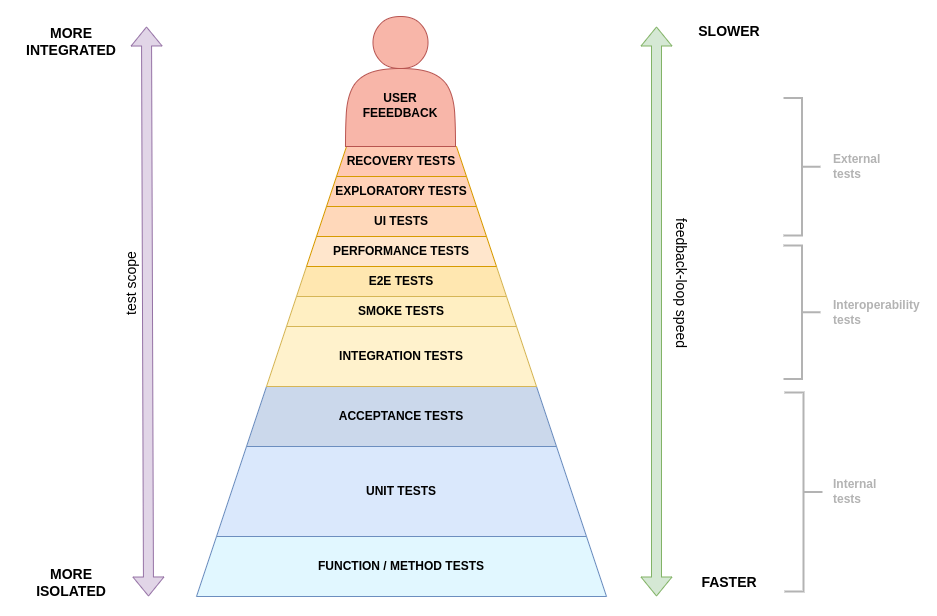

The Testing Pyramid is a concept in software development that categorizes different types of tests into a hierarchy, ranging from highly isolated tests at the base to fully integrated tests at the top. This framework helps ensure comprehensive software validation by balancing various testing strategies to achieve the desired software quality.

Key Components

- Functional Requirements: Specific features and capabilities that software must provide to meet user needs.

- System Characteristics: Operational and technical prerequisites and expectations of the software.

- Test Types: Different levels of testing from isolated unit tests to integrated end-to-end tests.

- Trade-offs: Balancing feedback speed, realism, and implementation time to achieve optimal testing coverage.

- Communication: Ensuring clear and effective communication about testing strategies, results, and implications for development.

Test Suite Structure and Characteristics

Think of tests as a series of experiments in the world of software development. Just like scientists aim to prove their hypotheses, software developers set out to prove that their code does precisely what it’s intended to do. Writing tests is our semiformal way of ensuring that the actual behaviour of our code aligns with our expectations.

Software development involves combining numerous small building blocks, arranging them in a way that molds the system into the desired behaviour1. Each of these building blocks must behave as intended. While validating individual components doesn’t guarantee the perfect functioning of the overall system, neglecting this step almost certainly guarantees failure.

There are various ways to validate software behaviour, ranging from highly isolated tests that scrutinize small code segments to user feedback forms, where users report any issues they encounter. The Testing Pyramid provides a structured approach to categorize these tests, ensuring a good balance between speed, realism, and implementation time.

Isolated tests are the most straightforward to create since they require minimal setup effort. They are fast to write and fast to execute. However, isolated tests are the most artificial type of tests, as they are the furthest removed from replicating real-world usage scenarios.

Integrated tests, on the other hand, are the most life-like scenarios we can create, simulating real-world usage. However, they demand substantial setup effort, making them more time-consuming and expensive to create and slower to execute.

tip:The testing pyramid provides insight into various test types, but it doesn’t imply that you should use all of them or that some are inherently better than others. Like many aspects of software development, your choice should align with your specific context.Ask yourself how much feedback speed and implementation time you are willing to sacrifice in exchange for additional realism.

A recommended heuristic is to aim for the fastest possible feedback loop that catches ~90% of issues.

Types of Tests

The Testing Pyramid encompasses various test types, each serving a specific purpose in the software development lifecycle. Here is an overview of the types included in the pyramid, from the most isolated to the most integrated:

Internal Tests

- Function/Method tests: These tests focus on verifying the behaviour of individual methods, offering fast and highly isolated feedback. They are typically used to validate core logic and handle exceptional cases.

- Unit tests: Testing specific “units of work,” which can encompass a set of methods or classes providing cohesive functionality to the system. While method-level tests are a subset of unit tests, the latter can involve multiple classes and methods, focusing on one main functionality while testing in isolation, minimizing the need for external functionality stubbing/mocking2.

- Acceptance tests: These determine when a particular feature is ready for deployment, spanning across multiple units to ensure correct implementation. It’s good practice to cover both expected “happy flow” and main “exception flow” cases in these tests. They are sometimes referred to as “service tests,” “contract tests,” or “customer tests” in specific architectures, where external interactions are stubbed out, but internal code is used.

Interoperability Tests

- Integration tests: These validate the connection to external systems, typically via a test implementation or a low-footprint approach. Integration tests are slower and more resource-intensive due to increased setup requirements. It’s advisable to limit the use of integration tests to specific cases.

- Smoke tests: Performed during system launch to ensure every component initializes correctly. They are not meant to test functionality but rather to provide minimal validation that the system is operational. Smoke tests are often executed before resource-intensive tests. If smoke tests fail, it indicates an issue during system initialization, and running further tests would be inefficient until the system stabilizes.

- E2E tests: End-to-end tests validate the entire system in a live environment, ensuring that all modules interact as intended and accurately representing real-world use cases. While valuable for comprehensive validation, they require substantial setup time and have a longer execution duration, resulting in delayed feedback, particularly for complex systems. These tests generally do not validate user interface logic and visuals but stick to using machine-to-machine entry points.

- Performance tests: Also referred to as “load tests,” these are end-to-end (E2E) tests that employ large volumes of data or requests to evaluate the system’s behaviour when subjected to heavy usage. Performance tests serve as a means to assess the runtime efficiency of your systems, particularly under extreme conditions, and to identify bottlenecks or performance degradation within the system.

External Tests

- UI tests: User Interface tests, often abbreviated as UI tests, belong to the category of end-to-end tests that interact with the system through its graphical user interface (if available). These tests require specialized tooling, such as browser-control software, to be executed automatically3. UI tests mimic user behaviour by navigating through the user interface, verifying that the UI accurately displays the expected results and maintains its intended appearance. However, UI tests are challenging to set up, have a lengthy execution time, and are known for their fragility, as even minor alterations to the UI structure can lead to test failures.

- Exploratory tests: These are manual tests aimed at uncovering unexpected behaviours or system properties that may not have been previously known. They are designed to reveal unusual situations, such as using extreme or nonsensical values, and are best conducted by individuals who were not directly involved in the system’s creation to avoid unintentional bias towards expected behaviours.

- Recovery tests: In simple terms, recovery tests involve intentionally disrupting (either partially or entirely) your system and observing how it recovers. The recovery process can be performed manually or automatically. Think of these tests as a fire drill for your software systems, helping assess their resilience.

- User feedback: While not always included in traditional testing approaches, user feedback is an invaluable source of insights. It provides information on how real end-users interact with your system, which features are meaningful to them, and common issues they encounter. However, this type of feedback typically occurs at the end of a release cycle and may not always be reliable.

Background

Origin

The Testing Pyramid concept was popularized by Mike Cohn in his book “Succeeding with Agile,” though the practice of categorizing tests into a hierarchy predates this. The pyramid metaphor helps developers visualize the need for a balanced approach to testing, emphasizing more isolated tests at the base and fewer integrated tests at the top.

Application

The Testing Pyramid is applied throughout the software development lifecycle to guide the creation and execution of tests. Developers use the pyramid to prioritize test writing, ensuring a strong foundation of unit tests, followed by integration tests, and a smaller number of end-to-end tests. This approach helps catch defects early, provides quick feedback, and ensures comprehensive system validation.

Comparisons

Automated Testing vs. Manual Testing

Automated testing uses scripts and tools for quick, repeatable results, aligning with the lower levels of the Testing Pyramid. Manual testing, often exploratory, aligns with higher levels, providing insights into user experience and identifying issues that automated tests might miss.

The Testing Pyramid vs. Monitoring and Auditing

The Testing Pyramid focuses on pre-deployment testing to ensure software quality and functionality. In contrast, monitoring and auditing involve post-deployment activities that track the system’s performance, detect issues in real time, and ensure compliance with standards. Both approaches are complementary; while the Testing Pyramid aims to catch issues before release, monitoring and auditing ensure the system remains stable and performs well in production.

The Testing Pyramid vs. Other Testing Frameworks

While the Testing Pyramid emphasizes a large base of unit tests, a smaller layer of integration tests, and a minimal layer of end-to-end tests, the Testing Diamond suggests more focus on integration tests with fewer unit and end-to-end tests. The choice between these approaches depends on the specific project needs and team preferences.

The Testing Pyramid is often compared with other frameworks like the V-Model, which emphasizes verification and validation through parallel testing phases corresponding to development stages. While the V-Model provides a structured approach to testing, the Testing Pyramid focuses on balancing different test types to optimize feedback and coverage. Additionally, frameworks like Behavior-Driven Development (BDD) and Test-Driven Development (TDD) emphasize writing tests before code, aligning closely with the Testing Pyramid’s emphasis on thorough and early testing.

Examples

Example 1: E-Commerce Platform

Imagine a development team working on an e-commerce platform. They decide to create a validation strategy using the Testing Pyramid. They start with a solid foundation of unit tests to validate individual functions and methods, ensuring core logic works as expected. Next, they add integration tests to verify the interaction between different modules, such as the payment gateway and inventory management system. Finally, they implement end-to-end tests to simulate real-world user scenarios, ensuring the entire checkout process works seamlessly from product selection to payment confirmation. Once the system is live, they collect user feedback through forms, complaints, and anonymized usage tracking, to identify pain points and areas for improvement. By prioritizing these test types, the team balances quick feedback with comprehensive validation, catching issues early and ensuring a smooth user experience.

Example 2: Healthcare Management System

In a healthcare management system, the development team faces stringent regulatory requirements and high user expectations. They employ the Testing Pyramid to structure their validation strategy. They begin with unit tests to validate critical functions like patient data encryption and access control. Integration tests are used to ensure the system interfaces correctly with external systems, such as electronic health records (EHR) and lab result databases. End-to-end tests simulate real-world scenarios, such as scheduling appointments and generating reports, to validate the entire user workflow. Additionally, the team incorporates manual exploratory tests to identify edge cases and recovery tests to assess system resilience.

They then move on to an “alpha release” where a select group of users test the system in a controlled environment, providing valuable feedback for further improvements. This is followed by a “beta release” to a broader user base, gathering additional insights. As part of the beta release, the system is scrutinized through performance tests to ensure it can handle the expected load and maintain responsiveness, and given a complete penetration test to identify potential security vulnerabilities.

Further Exploration

- Fowler, M. (2018). The Practical Test Pyramid. MartinFowler.com.

https://martinfowler.com/articles/practical-test-pyramid.html. - Cohn, M. (2010). Succeeding with Agile: Software Development Using Scrum. Addison-Wesley. isbn: 0321579364.

https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/6707987-succeeding-with-agile. - Kaner, C.; Bach, J.; Pettichord, B. (2001). Lessons Learned in Software Testing: A Context-Driven Approach. Wiley. isbn: 9780471081128.

https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/lessons-learned-in/9780471081128/. - Beck, K. & Andres, C. (2004). Extreme Programming Explained: Embrace Change. Addison-Wesley. isbn: 9780321278654.

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/67833.Extreme_Programming_Explained. - SE Daily podcast (2019). Facebook Engineering Process with Kent Beck. Software Engineer Daily.

https://softwareengineeringdaily.com/2019/08/28/facebook-engineering-process-with-kent-beck.

Decomposing functionality into smaller blocks is often called “divide and conquer”, referencing Caesar’s famous strategy in The Gallic Wars (58-50 BC). ↩︎

Being too strict in your definition of “Unit Tests” can lead to difficult-to-maintain code, as it commonly pushes people towards structural testing (i.e. verifying a certain method calls another method). This will make future refactoring and restructuring a lot more difficult. In general, write your tests as if you are unaware of the internal structure of your code. If you decide to extract part of the functionality in a class to a composite object (helper class), there should be no effect on your test suite. ↩︎

The most common web=based UI test frameworks work by parsing their HTML DOM-tree and using identifiers or position-based logic to perform user interaction. If you make some visual changes to your web application, such as moving a menu around, or changing the order of elements, these tests tend to break in spectacular fashion. As they are difficult to set up and maintain, and tend to result in false-negative issue reports, developers tend to avoid using them. Have a look at cypress.io or selenium.dev if you are interested in learning more about this type of tests. ↩︎